Kindly contact us via email info@mof.com.sg or whatsapp (click on below) to tailor make a program for you, your company, club or school. We do that weekly at affordable prices for all groups of people! There are basic and advanced programs, small or larger groups, one-off activities or weekly customized programs etc. etc.

info@ministryoffootball.com.sg

https://api.whatsapp.com/send?phone=6592799006

Contact us at for more information ! The below gives you an idea of what our program will be like!

Introduction & basic pointers from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tai_chi

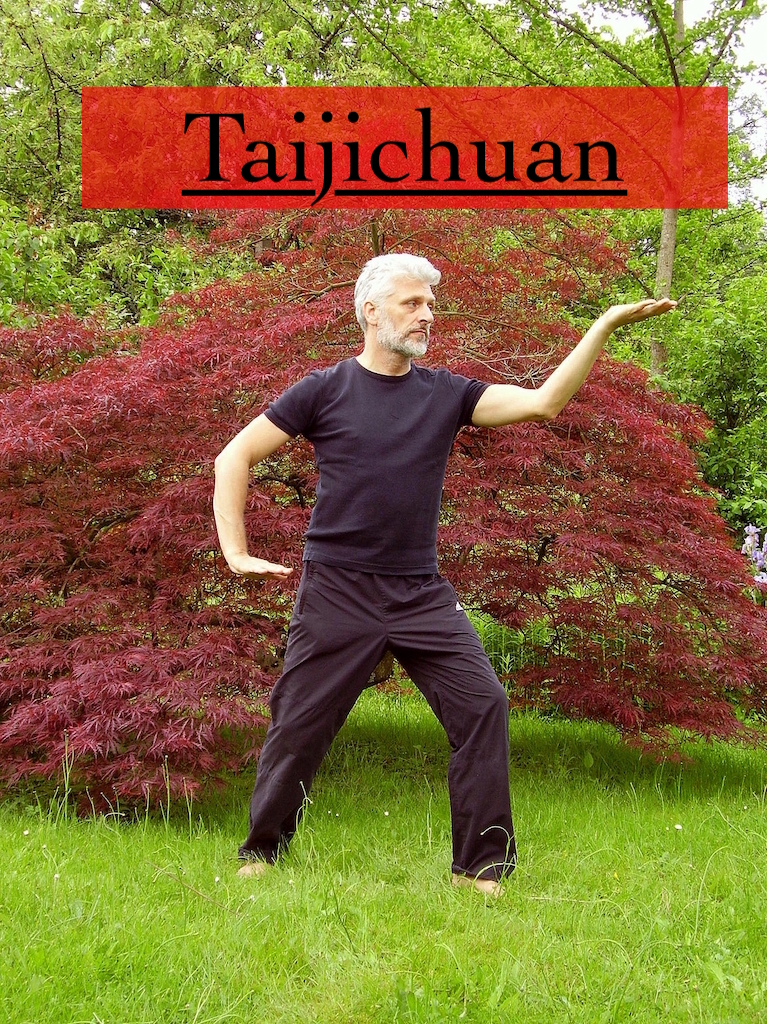

The concept of the taiji (“supreme ultimate”), in contrast with wuji (“without ultimate”), appears in both Taoist and Confucian Chinese philosophy, where it represents the fusion or mother[1] of yin and yang into a single ultimate, represented by the taijitu symbol ![]() . Tai chi theory and practice evolved in agreement with many Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism.

. Tai chi theory and practice evolved in agreement with many Chinese philosophical principles, including those of Taoism and Confucianism.

Tai chi training involves five elements, taolu (solo hand and weapons routines/forms), neigong and qigong (breathing, movement and awareness exercises and meditation), tuishou (response drills) and sanshou (self defence techniques). While tai chi is typified by some for its slow movements, many styles (including the three most popular: Yang, Wu and Chen) have secondary forms with faster pace. Some traditional schools teach partner exercises known as tuishou (“pushing hands”), and martial applications of the postures of different forms (taolu).

In China, tai chi is categorized under the Wudang grouping of Chinese martial arts[2]—that is, the arts applied with internal power.[3] Although the term Wudang suggests these arts originated in the Wudang Mountains, it is simply used to distinguish the skills, theories and applications of neijia (internal arts) from those of the Shaolin grouping, or waijia (hard or external) styles.[4]

Since the earliest widespread promotion of the health benefits of tai chi by Yang Shaohou, Yang Chengfu, Wu Chien-ch‘üan and Sun Lutang in the early 20th century,[5] it has developed a worldwide following of people, often with little or no interest in martial training, for its benefit to personal health.[6] Medical studies of t‘ai-chi support its effectiveness as an alternative exercise and a form of martial arts therapy.

It is purported that focusing the mind solely on the movements of the form helps to bring about a state of mental calm and clarity. Besides general health benefits and stress management attributed to tai chi training, aspects of traditional Chinese medicine are taught to advanced students in some traditional schools.[7]

Some other forms of martial arts require students to wear a uniform during practice. In general, tai chi schools do not require a uniform, but both traditional and modern teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.[8][9]

The physical techniques of tai chi are described in the “T‘ai-chi classics“, a set of writings by traditional masters, as being characterized by the use of leverage through the joints based on coordination and relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in order to neutralize, yield or initiate attacks. The slow, repetitive work involved in the process of learning how that leverage is generated gently and measurably increases, as well as opens, the internal circulation (breath, body heat, blood, lymph, peristalsis).

The study of tai chi primarily involves three aspects:

- Health: An unhealthy or otherwise uncomfortable person may find it difficult to meditate to a state of calmness or to use tai chi as a martial art. Tai chi’s health training, therefore, concentrates on relieving the physical effects of stress on the body and mind. For those focused on tai chi’s martial application, good physical fitness is an important step towards effective self-defense.

- Meditation: The focus and calmness cultivated by the meditative aspect of tai chi is seen as necessary in maintaining optimum health (in the sense of relieving stress and maintaining homeostasis) and in application of the form as a soft style martial art.

- Martial art: The ability to use tai chi as a form of self-defense in combat is the test of a student’s understanding of the art. Tai chi is the study of appropriate change in response to outside forces, the study of yielding and sticking to an incoming attack rather than attempting to meet it with opposing force.[10] The use of tai chi as a martial art is quite challenging and requires a great deal of training.[11]

There are five major styles of tai chi, each named after the Chinese family from which it originated:

- Chen style (陳氏) of Chen Wangting (1580–1660)

- Yang style (楊氏) of Yang Luchan (1799–1872)

- Wu Hao style (武氏) of Wu Yuxiang (1812–1880)

- Wu style (吳氏) of Wu Quanyou (1834–1902) and his son Wu Jianquan (1870–1942)

- Sun style (孫氏) of Sun Lutang (1861–1932)

The order of verifiable age is as listed above. The order of popularity (in terms of number of practitioners) is Yang, Wu, Chen, Sun and Wu/Hao.[4] The major family styles share much underlying theory, but differ in their approaches to training.

There are now dozens of new styles, hybrid styles, and offshoots of the main styles, but the five family schools are the groups recognized by the international community as being the orthodox styles. Other important styles are Zhaobao tàijíquán, a close cousin of Chen style, which has been newly recognized by Western practitioners as a distinct style; the Fu style, created by Fu Chen Sung, which evolved from Chen, Sun and Yang styles, and also incorporates movements from Baguazhang (Pa Kua Chang)[citation needed]; and the Cheng Man-ch’ing style which is a simplification of the traditional Yang style.